Dear readers,

I’ve been thinking about Jeju 4.3 and what still remains unresolved. I've tried to put my thoughts to paper and share some reflections on this occasion. Grateful to those who continue to reflect on this history and engage with its memory, today and always.

Best,

Jack

Reflections on Jeju 4.3 and Korea’s Incomplete Reckoning with History.

We are now just over 24 hours away from the Constitutional Court’s verdict in the impeachment trial of Yoon Seok Yeol. The decision will shape the country’s democratic trajectory, which was threatened by his failed invocation of martial law four months ago and the crisis that ensued. Day after day, citizens have endured social and political turmoil, hoping for justice and the chance to turn a new page.

This momentous decision nearly coincides with today’s 77th anniversary of Jeju 4.3, a tragedy that began on March 1, 1947, and continued until September 21, 1954. While many have a certain awareness of Jeju 4.3, it is often treated as a settled matter, a dark chapter of history that has long been concluded. This assumption, however, is misleading. The reckoning should have happened decades ago. And yet, here we stand, still facing denial, still uncovering the remains of victims, still waiting for truth to meet justice. This unfinished reckoning is not due to a lack of evidence. Years of investigations, testimonies, and academic efforts have shed light on historical facts. The deeper issue is ideological resistance, deeply rooted in the Cold War, which views truth not as a necessity for progress but as a threat to the status quo.

Why, after decades of truth commissions, exhumations, and memorialization, does Jeju 4.3 remain contested? Because it is not merely about the past; it is about the present and the future. It is about who controls the narrative of the nation, whose suffering is acknowledged, and whose is dismissed. The massacre sites, where Jeju prisoners were executed alongside others, remain unexcavated on the mainland. This is not due to a lack of resources but a lack of political will. When excavations like those at the Gyeongsan Cobalt Mine have stalled since 2009, the reason is clear: a refusal to confront uncomfortable truths.

Meanwhile, remains that have been exhumed languish in storage, awaiting DNA identification that could take decades. This is not due to technological or financial constraints, but because acknowledging these victims would also require confronting the historical perpetrators and the chain of command that enabled these atrocities. While the individuals responsible may no longer be alive, the systems of power, the ideologies that justified these acts, and the refusal to fully reckon with the past continue to shape the present. The skeletal remains of these victims, exhumed but left unidentified, await the closure that only recognition and proper rites can provide.

Research into the massacres before and after the Korean War, including Jeju 4.3, reveals a troubling pattern. These are not isolated incidents but part of a broader system of state violence and crimes against humanity. The National Guidance League massacres, where up to 330,000 people, leftists, suspected leftists, and apolitical citizens, were systematically executed, serve as a stark example. Despite the facts being known, forces continue to suppress, deny, and rewrite history. These massacres, carried out under the guise of anti-communism, are part of an ideology still entrenched in South Korea’s national security framework.

The National Guidance League’s members, including of whom were unaware they had been enrolled, were promised integration into the nation but were surveilled, monitored, and ultimately killed. Today, bereaved families who have spent decades seeking the truth are being subjected to reinvestigation by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Rather than being recognized as victims, some are being rebranded as collaborators based on dubious documents that lack legal credibility. This revisionism is a clear attempt to shift blame and rewrite history, further marginalizing victims and erasing the inconvenient truth of state-sponsored violence.

Regardless of political affiliation, no human being deserves to be eradicated for their beliefs. Yes, some leftists joined guerrilla movements, but we must understand the circumstances that led them to do so and confront those realities without distorting history or creating hierarchies of victimhood. The issue is not ideology. It is the refusal to grant a fair trial to those who were massacred in the name of anti-communism.

Adding to this erasure is the looming threat that the remains of massacre victims may be jointly interred and cremated, destroying the physical evidence that could provide irrefutable proof of these crimes. While no definitive decision has been made, the consideration of such an act, framed as a practical solution or a gesture of respect, would obliterate forensic evidence, further obscuring responsibility. For many bereaved families, this is not just about burial. It is about burying history itself.

Conservative forces argue that dwelling on past violence weakens national unity, that reopening these wounds causes unnecessary division. Some still justify state violence during Jeju 4.3 and beyond as a necessary measure against communist infiltration, a justification deeply rooted in Cold War-era thinking. Admitting that the South Korean government engaged in widespread civilian massacres would call into question the righteousness of its anti-communist mission and the legitimacy of its post-war authoritarian rule. For some conservative factions, this challenges the historical narrative that has long underpinned their political legitimacy, particularly given the enduring role of the United States in South Korea’s security framework. They may also fear that addressing these dark chapters would detract from the focus on North Korea’s ongoing human rights abuses. But why must we choose? Why can’t both truths coexist?

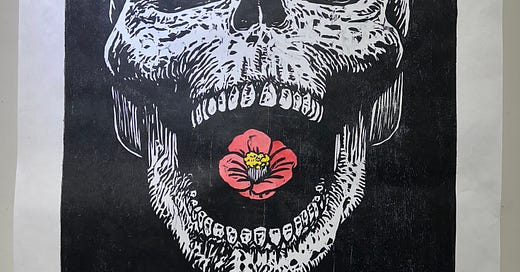

While I often find myself frustrated watching political institutions falter, legal processes stagnate, and hard-won advancements backslide with shifting political currents, I take solace in the works of artists and writers who stand as allies in the fight for historical justice. Through woodblock prints, paintings, novels, films, and documentaries, they break through walls of denial with raw imagery and human stories. From Kim Seok-beom’s Volcano Island to Han Kang’s We Do Not Part, from Bak Kyung-hoon’s woodcuts to contemporary painting and media installations, the arts have kept Jeju and other civilian massacres of the Korean War alive in public consciousness. When politicians refuse to acknowledge the past, art compels contemporary audiences to bear witness. It ensures that even when commissions dissolve and funding is cut, memory persists.

History and progress do not have to be mutually exclusive. Spain, Argentina, and Germany have all pursued truth while continuing to build their futures, proving that reckoning with the past does not weaken a nation. These countries are not perfect, and reconciliation is often contentious. But avoiding historical accountability only deepens divisions, allowing the past to fester and reemerge as new crises. This is evident in the recent martial law controversy. The argument that moving on is necessary for unity is selective and convenient, applied only when the victims are inconvenient to the dominant national narrative.

This is not merely about victimhood. Jeju 4.3 is a story of survival, resistance, and the ongoing struggle for justice. Survivors and their families have fought for decades to uncover the truth, demanding recognition not as collateral damage of war but as human beings whose suffering and trauma under a system of guilt by association must be acknowledged. Their struggle mirrors that of families across the world, from Argentina’s Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo to Spain’s families searching for victims of Franco’s regime, and countless others who refuse to let their histories be erased.

As I sift through documents, listen to the bereaved, and reflect on diverse perspectives, I am keenly aware that this is not my history. I am not Korean, and I do not seek to lecture. I simply want to reflect on what I have observed and share as broad a truth as possible. My role is small, and all I hope is to help those whose voices were silenced for so long finally tell their stories without fear before they can no longer do so themselves.

Why must Jeju 4.3 and its related events remain in our collective memory? Because the struggle continues. Because the past lingers unresolved. Because every unmarked grave asks a question still unanswered. Because we owe it to those who fought for truth to ensure their struggle was not in vain. And because justice, however delayed, remains worth pursuing.

This is not about deepening divisions. Rather, it is about recognizing that true reconciliation demands time, persistence, empathy, and a collective commitment to historical truth. We must find ways to coexist and move forward with respect, even when we cannot see eye to eye. We must continue to reopen the door to reckoning with the truth, to validate the experiences of those affected, and to hold accountable those responsible in a way that fosters growth, future cooperation, and healing, rather than fueling further conflict through retribution.

Photo: 박경훈의 동백 (Camellia) 한지 위에 목판, 100 by 60 cm, 2025. Currently on display at 갤러리 나무.